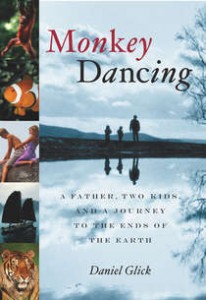

(PublicAffairs)

The Idea

After my older brother died from breast cancer and my marriage ended, my ex-wife moved to another state to live with her new girlfriend. Lost in an emotional wilderness, I found myself raising our two young children alone, trying to make sense of these abrupt changes — to myself and to my kids. Torn by these dual shocks, I embarked on my odyssey into single fatherhood in an admittedly unusual way: by taking my kids on an extended journey around the world.

I had broached the idea with my brother as he was dying, and although the thought of traveling through Asia with two young kids closely approximated his idea of hell, he allowed that it might work for me. As I thought about it, I figured that we could utilize our adventure as a crucible to forge a new family unit. With my brother’s passing as an impossibly sad inspiration, I made plans to set off.

In the bizarre aftermath of my divorce, I felt as if I had been granted a unique window of opportunity to do something crazy, since all our routines had been abruptly disrupted anyway. I decided we’d focus our trip by visiting some of the world’s rare life forms before they disappeared from the planet, and hastily planned the trip to begin before the kids themselves would grow up and chart their own paths.

I privately thought of our journey as a “Before they’re gone‚” tour. The literal meaning was to visit amazing critters and places before humans maimed or destroyed them. The second was to spend time with my children before they left my reconfigured single father’s nest. Lastly, the big “before they’re gone” loomed especially large: after witnessing my brother die at 48, I knew viscerally there were no guarantees about how long any of us would be around. It was time to do something drastic, and I nominated an epic road trip.

In the summer of 2001, nine-year old Zoe, thirteen-year old Kolya and their forty-four year old dad took off from Colorado for a five-month journey on which we would seek out Maori wrasses in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, orangutans in Borneo, Javan Rhinos in Vietnam, Bengal tigers in Nepal, and more. Meeting countless challenges — emotional, logistical and physical — the three of us shared experiences we could not have imagined and would not soon forget. We watched in horror from a dingy hotel in Singapore as the World Trade Center buildings collapsed, and continued on our trip with the much-changed perspective of apprehensive Americans abroad. We braved pythons, pit vipers, leeches, mosquitos, insane taxi drivers and each other on the way to becoming much different people than the ones who started the trip.

The book weaves accounts of our encounters with the natural world — and each other –with intimate reflections on my own reckoning with loss, change, and fatherhood. On the way, I try to illuminate the connections between our relationships with each other and our relationship with the earth we inhabit.

For anyone who dreams of traveling to the world’s most exotic places, for anyone already navigating that wild journey called parenting, for anyone who has endured loss and grief and searched for a way out, I invite you to join us on our multi-layered journey.

EXCERPT

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT, after my daughter Zoe woke me for the third time because she was afraid of the snakes, I wondered, not for the first time, whether this trip had really been such an inspired idea. Earlier, Zoe had been complaining about leeches, and before that mosquitoes, and it dawned on me that unless you were raised in the rainforest, accustomed to strangler figs and spiders the size of gerbils, Borneo was a pretty forbidding environment. For a nine-year old girl reared in suburban Colorado, this place looked downright menacing. My thirteen-year old son Kolya, also awakened by his sister, didn’t help things when he authoritatively informed Zoe that since she was the smallest mammal among us, any predator would obviously eat her first.

I shot Kolya a venomous look that temporarily silenced him, and reassured Zoe that it was unlikely that snakes could board the 55-foot houseboat (called a klotok) where we were sleeping, moored on the banks of the Sekonyer River in southern Kalimantan. She wasn’t persuaded. Zoe knew the serpents were lurking. Heading upriver earlier that afternoon, past suffocating green jungle crawling from riverbanks and proboscis monkeys hanging from trees like misshapen, mischievous fruit, a sudden movement in the water had caught our eyes. Peering ahead, we felt certain it was a crocodile. We were wrong. The animal’s head, although almost as big as a crocodile’s, belonged to a 20-foot long python, with a body circumference only slightly smaller than my thigh. We gaped with disbelief as the python disappeared into the murky water, leaving deceptively minor ripples.

As the ripples receded, we became especially attentive to other motion in the silty ribbon of river that carried us deeper into the jungle. I felt acutely aware of the reassuring diesel engine chug that muted the unfamiliar and suddenly ominous chirps and creaks and rustles emanating from the overgrown banks. We moved forward from the deck, shaded by a blue plastic canopy jerry-rigged on metal poles, and positioned ourselves on the bow like sentries. Within five minutes, we spotted another serpentine motion in the river and glimpsed a much smaller bright green reptile with a classic triangular-shaped head, slithering with startling speed toward the port-side shore: a pit viper, one of the world’s most poisonous snakes.

I held Zoe’s hand, tried to convey my amazement rather than fear. In the space of five minutes we had seen proboscis monkeys, with their bulbous, clown-like noses, a species that didn’t live anywhere else on the planet — as well as a python and a pit viper. This was what it was all about for me, heading upriver into Heart of Darkness territory with my two children, a voyage to the headwaters of grief, loss and — who knows? — possibly even the source of healing and grace after such momentous transitions in our lives.

Monkey Q&A — the author questions himself

Q: Okay, I’ll bite. What’s “monkey dancing?”

A: I don’t suppose I could tell you to read the book?

Q: I promise to read the book even if you tell me.

A: I can live with that. “Monkey dancing” was actually my son Kolya’s expression. We had been backpacking on a wilderness rainforest island in Australia for four days, and camped our last night on a deserted white sand beach. After dinner, the kids called me to join them near water’s edge, and the two of them jumped me. We began a raucous three-way tag-team wrestling match that mostly involved the kids running kamikaze at me and me tossing them to the sand like a benevolent King Kong. It was a wonderful, warm, tropical night, and without a word, we started a kind of simian step, hunching our shoulders up and down and dragging our knuckles on the fine sand. The three of us peered at each other with cocked heads, and started making monkey sounds. We started moving slowly, almost in a circle, then faster, and faster, with more abandon and less inhibition. Soon we were dancing wildly along the beach, rolling around, jumping and screaming. Kolya dubbed it “monkey-dancing.” And it stuck.

Q: Why make that the book’s title?

A: I guess it just became a metaphor for the trip. Monkey dancing meant wild abandon, it meant adventure, it meant the three of us creating something new together. When our first spontaneous monkey dance erupted on that Australian beach, three weeks or so into the trip, I took it as a sign that something remarkable was being born: a new family of three.

Q: Good lead in to my next question. After your divorce, your wife moved a thousand miles away. A year later your brother died of breast cancer. A lot of people would have crawled under the covers and started hoarding Prozac. You decided to go to Borneo. Why?

A: After a treacherous passage through the past few years, a long, open-ended journey had beckoned to me like a Siren’s song. Hitting the road had always served me in times of transition as an entrée into a reflective trance, as a tool of personal reinvention, as literal and metaphorical escape. For much of my life, I had sought psychic salve in the thrill of discovery amidst wild, unfamiliar places, and among unpredictable traveling companions. Borneo certainly qualified as wild and unfamiliar, and my two children effortlessly supplied the unpredictability.

Q: How about your concerns for your daughter when she freaked out after seeing the python and pit viper?

A: I realized the irony that as I was trying to show my kids more about the natural world, at times I made them a little more fearful of it. Leeches, mosquitoes, scorpions and poisonous snakes aren’t the earth’s most cuddly creatures. We did, however, see koala bears, kookaburras, wallabies, cassowaries, kangaroos, rhinos, elephants, mongooses, orangutans, macaques, proboscis monkeys, and other pretty cool animals.

I’d be lying if I said the trip wasn’t challenging and immensely difficult at times. Of course I was concerned about my kids’ fears of the unknown and unfamiliar. Kids are full of fears, as we all are. Snakes and voracious jungle predators that make little girls disappear without a burp can be scary. I grappled with my fears that the kids would contract malaria or get lost in Phnom Pehn. If you’re asking, “Did I ever consider calling the whole thing off?” the answer is, “Yes, several times.” But that feeling never lasted long, and now I think the kids are very proud of themselves for doing what we did. So am I. One thing I hope to teach my kids is to make peace with their fears, to stare them in the eye without blinking. Even with that fatherly advice, however, Zoe still made me look under the bed for googly-monsters before I said good night for many years.

Q: What about after September 11, 2001? Did you feel safe being Americans abroad?

A: The response after 9/ 11 was universally heart-warming. We were in Singapore, and a couple days later we headed for Vietnam. People expressed outrage at the terrorist attacks, and solidarity with the U.S. We were made to feel very much a part of the world community. As the weeks and months went by, though, some people shared their concerns about President Bush’s apparent disdain for world opinion. I grew very fearful myself, since our country was being guided through perilous international waters by a man who had spent less time abroad than my nine-year-old daughter.

Q: Can we talk a little about writing? You had predominantly been a newsmagazine journalist, and your first book was an investigation of a true crime story, the so-called “ecoterrorism” attacks at Vail ski resort in 1998. What is it like writing such a personal story?

A: Talk about scary. In twelve years of working for Newsweek, I used the pronoun “I”exactly twice. It’s daunting writing about people I know, about my family, about my own losses and failings. But I realized early on that this book had to be as honest as possible in order to work, so I guess I had to stare my own fears down, too. You may have noticed that I did manage to slip in some old-fashioned environmental reporting about the perilous condition of coral reefs, orangutans, Javan rhinos, and tigers.

Q: You write about your brother, about environmental issues, about parenting, about relationships, about your own inner and outer journeys. The book covers a lot of ground. Where do you think this book belongs in bookstores, anyway?

A: On the must-read, innovative non-fiction, travel, memoir, parenting, environmental table, of course. The book does cover a lot of ground, and my hope is that it will draw people into a genre they might not ordinarily visit. Obviously one main narrative thread is about our literal odyssey around the world: We went to some truly memorable places and met some incredible people. The book is a memoir as well, since I do draw on my own experiences growing up in Africa with my brothers, as well as being with my older brother as he was dying. As I said before, there’s also some straightforward journalism about our troubled relationship with the natural world. I can’t really say it’s a self-help book, but I hope that some people might find courage and solace from my journey through loss and grief towards something like hope and redemption. And lastly, I’m betting that anybody who is a parent will find some hilariously familiar and thought-provoking lessons here.

Q: Have do the kids feel about it now that they are both adults?

A: The trip was a turning point in all our lives: Before and after the Monkey Dance. We’ve had a lot of adventures together since then, notably living in Algeria together and

going on a camel trek in the Sahara with Touareg tribesman — and they’ve both set out on their own adventures. Both of them ran with the bulls at the fiesta de San Fermin in Pamplona, for example, which I did not think was a particularly bright idea. But they were both active participants in the book back then, and both of them offered up their journal entries. I think they’re very proud of what they’ve written, and what we did together. I’m certainly proud of what they’ve written. Some of their insights and observations went way beyond their years. I also suspect they’ve learned a few things about their father they didn’t know. My hope is that they’ll see it on some level as a love letter from their dad. Which it is.

Reviews

“Glick’s journalistic background informs his odyssey with a sense of scholarly urgency…Even the most dangerous encounters are leavened by Glick’s mordant sense of humor: “The kids returned, uneaten.”

The New Yorker “Book Currents”June 16 & 23, 2003

“His rich narrative traces their five-month sojourn, a trip filled with wonder and awe, kids bickering and whining, uncomfortable lodgings combined with exotic foods, the hassles of travel balanced against the joys of discovery.”

Los Angeles Times July 8, 2003

“This unusual, superbly written and deeply human story of their travels is a consistently rewarding odyssey.”

Publishers Weekly May 15, 2003 Starred Review

“[A] big-hearted, pleasingly fitful narrative of the kind of journey that scours the soul of its karmic gunk.”

Kirkus Reviews April 15, 2003

“An engaging and moving narrative that informs as it entertains…A fine blend of travel and inspirational writing.”

Library Journal May 1, 2003

“This is much more than a simple travel story. Glick’s memoirs…explore the connective tissue of familial, environmental, political and universal relations.

Boulder Daily Camera May 31, 2003

An Amazon.com “Spring Breakout Books” selection and “Best Books of 2003: Top 50 Editors’ Picks”; a USA Today “Sizzling Summer Reads” selection and Child Magazine’s pick for “Best Books About Being a Dad”